Family traditions still form the core of the Roma culture. They are still very much present and alive nowadays, even when the Roma do no longer live a “traditional” live.

These traditions are extremely intricate. They are based on the respect of elders and especially of older women (phuri daj or phuri dej). One can only barely give an outline of these traditions here.

Birth

There are many traditions around birth. In some travelling Roma groups, the mother gives birth in a special tent, which will then be destroyed. For the first few days, only the mother and some other women attends or see the child. One presents the child formally to the family after a few days.

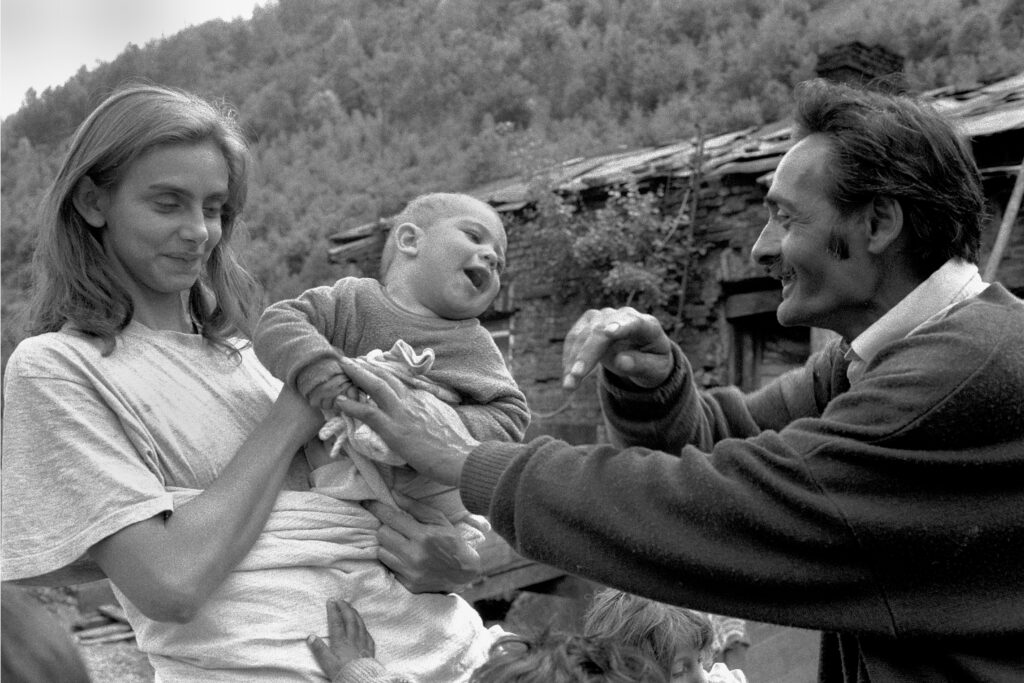

Baptism

Baptism, bolimos or bolipe in Romanes, is an important ceremony and the child gets his formal name. All members of the family as well as many members of the clan are present on this occasion. The parents choose godfather and godmother (kirvo/kirvi) from highly regarded members of the extended family.

The baptism takes place in church and after that, people attending (sometimes up to 200-300) party, eat, drink and have fun. They give the child expensive presents. From that moment onward, the god-parents take an important place in the life of the child, as second parents, helping him in all difficult or important moments of his or her life.

The Muslim Roma in the Balkan of course do not have baptisms. They have other traditions, for a boy the suneti – circumcision. They call the feast after the operation the sunetjeskoro bijav – lit. the circumcision wedding! As for the Christian Roma, the entire family as well as friends and relatives of the mahala, meet and eat, drink, dance and give presents to the child.

Children

The biggest responsibility about children naturally is the mother’s. Children are much freer to do as they please than the children of non-Roma. The freedom of girls shrank rapidly, latest as soon as their mother had another child. From then on, a girl had to help her mother raise her siblings, even sometimes when she was as young as 7 years.

Gender roles are traditionally set early. Girls help their mothers for household chores , cooking, washing clothes etc. A girl will also traditionally follow her mother when she goes to villages to sell things or to go fortune telling. Boys help their fathers and other men in traditional trades. Smith work, tinning, tending horses, and so on.

This is not to say that no Roma child goes to school. In fact, they all do, and many have completed a university degree. Due to stereotypes among the general population about Roma, schools are a difficult period for Roma children. They face racism, exclusion, discrimination, and also need to help at home.

Bethrothal

Historically, among Roma (as among others), weddings did traditionally occur at an early age – for boys, between 15 and 17, for girls between 14 and 16. As weddings are seldom official even today, marrying means effectively living with someone. De-facto, among Roma, the first boyfriend or girlfriend is the husband or the wife.

This is changing or has already changed among most Roma. Nowadays, they marry not really earlier nor later than the general population.

Within the Roma community, Roma tell each other who is of the right age to marry. This leads to potential bethrotals. The father and mother of the bridegroom (to be) sometimes pay a visit to the parents of the girl. The parents of the boy look for a future daughter in law who is beautiful, resourceful and from a well known family and clan. Should either side find either the boy or the girl not to their liking, they’ll simply refuse the match. The choice and ultimate decision rests on the parental side. Among Kalderaša, there are sometimes early agreements of betrothal, when the children are sometimes still in the cradle. In any case, should the wedding not take place, the parents of either the boy or girl will have to pay a fine.

Should they (and both the bride and groom to be) like the match, the ceremony – called among Vlach Roma mangavimos lit. the proposition- corresponding to a betrothal can begin.

Among all Roma groups another tradition exists: the flight of the young couple when parents haven’t formally agreed to a wedding. After a few days, the young couple returns in their clan and one then celebrates the wedding. In some Roma groups, a symbolic form of this abduction is still exists.

Taboos

One thing is a clear taboo among Roma: Incest. For Roma, to marry a second degree cousin is already incest. Among Roma who lived in villages, the old adage said that one should only marry people from at least two villages away.

This has led many Roma to marry outside their community. The rule being that if the consort integrates in the Roma community, there is no issue, and the children are of course Roma.

Paying for the Bride

One of the favourite subjects of journalists and a very common stereotype is that Roma buy their brides. One should actually use “pay for” rather than “buying” in this context. This is almost exclusively found among Vlach Roma. Even now, this tradition has remained very much alive among them, especially so among the Kalderaša. The price is always paid in gold coins, never in banknotes. Prices of two or three hundred gold coins are not unusual. The father of the bride receives the coins and generally, these pass to to the bride. Among Kalderaša, these coins are worn in the seams of their heavy dresses.

Wedding

Once all parties agree, the wedding can go ahead. In Romanes one calls a wedding bijav or bjav (sometimes abav, abjav).

On the wedding day relatives from the settlement and even further, from other villages or cities are present. There is an abundance of food and drinks, presented by the parents of the newlywed. From the wedding onward, the two sets of parents are considered to be related, under the term xanamik, father/mother of the son/daughter in law. In spite of not being blood ties, the concept of xanamik is a very important one among Roma.

At the wedding, all the guests give gifts to the newly-wed, sometimes even money and they return the politeness by giving small gifts to them. Of course, all guests sing and dance. The wedding ceremonies culminate when the young couple retires to their room (it used to be a special tent among travelling Roma) where they’ll consummate the union.

Traditionally, all guests waited for the result – the blood traces proving that the girl was a virgin, thus demonstrating to all guest she was honourable. Sometimes, the bloody clothes were hung on a high place, to be looked at by any passer-by (one used to hang them on the top most tent pole). After this, the feast continues with renewed vigour. Should the girl not have been virgin, this disgraces her entire family and parents. They have to repay the dowry.

A wedding lasts a minimum of three days. Nowadays, in cities, the wedding non longer take place at home but rather in a restaurant, where 200-300 guest are often present.

Among Muslim Roma in the Balkan, the ceremonies take place as described, but with some Balkanic and Turkish elements in the ceremony (for example, the friends of the bridegroom bring him to the baths, cut his hair and shave him etc.).

Married Life

After the wedding, the girl wears a scarf over her head. She is not free to show her hair to others than her husband – this would be a big shame. This tradition is slowly disappearing.

The bride traditionally goes to live in her husband’s family but the father and the mother of a bride nevertheless keep an eye on her life in her new family . Should anything untowards happen to her, should for example her husband beat her or otherwise mistreat her, should she have worries, her parents may take her back home for a while or definitively. In those case, they do not have to repay the dowry they received for their daughter.

Divorce

Divorce is allowed among Roma. One can divorce for many reasons, even for simple incompatibility or mutual consent. Other reasons include the husband not supporting the family, fights, etc. In Poland where the catholic church is prevalent, divorces are less common. For Vlach Roma, divorces are complicated by the need to reimburse the price of the bride.

Divorces happen by mutual consent or are judged in front of a Kris. Once divorced, both are free to marry again.

Death and Burial

Kalderaša have some of the most intricate traditions on death and burial. When – as the Roma say “God forbids”, someone dies in the family, his close relatives buy the coffin and lay the dead in his best clothes inside it. Beforehand, one measures the dead with a ribbon, graduated in centimetres, called mesura. The family keeps mesura as a talisman protecting the family against all bad things and unhappiness.

Objects dear to the deceased such as watch, comb, cigarettes or other cherished possessions will accompany the deceased in his coffin. Matches cannot be put there, for fear the deceased may come back and burn the house. This is all done to prevent the deceased to come back for his belongings. Some Roma groups, for example the Sinti, simply burnt all the deceased possessions or sold them to Gadže.

For three days, the deceased and the coffin remain at home. For three days and three nights, his family sit at his side.They light candles, drink wine or alcohol. But candles and bottles have to come in odd numbers. Unshaved men, uncombed women sit beside the deceased, eat drink and tell each other stories and tales.

On the fourth day, the deceased is carried to the cemetery, always feet ahead. All the recipients in the house are then emptied of water, for fear that the deceased soul – always thirsty, may come back at night to the house.

Among many Roma groups, the family cannot dance, sing, or play an instrument for a full year after the death of a family member.