What is Roma music?

What is Roma music? This seemingly innocuous question has fed quite an industry. From the 18th century onward, musicians, scientist have tried to answer this question and only partially lifted the veil. This essay, without scientific pretension, is the result of our work with Roma from different regions and of listening to hours of archives and musicians. It just aims to provide a glimpse of what we’ve learned to recognise as Roma music.

So what is Roma music? What are the common threads and the common points between say, Flamenco, Hungarian Gypsy Music and Balkan Wind Orchestras? For even though Roma all came from the same country, India, speak the same language – local variations notwithstanding – have common laws and traditions, their music varies tremendously from region to region and from group[1] to group.

There are nevertheless characteristics which represent what one can call Roma music.

There are 5 main characteristics of Roma music trancending the local musical traditions. Some of these are obvious, some more subjective which sometimes makes it hard to “scientifically” describe them. What are they? Without formal musical schooling, one can call them, rather arbitrarily, voices, timing, phraseology, harmonies and singing.

Voices

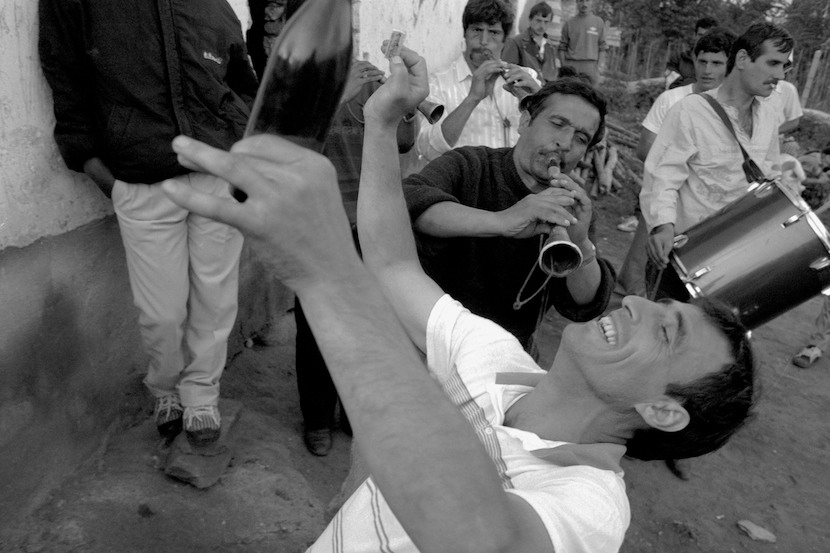

The first and for me foremost characteristic of Roma music is the presence, in one way or the other of three voices in every song, sometimes only in parts of them. These voices are either sung or played by instruments. Typically, the three voices are the melodic line, the terce and the quint. Russian Roma traditionally sing these and use instruments only to provide the rhythm and harmonies. In the Balkan, quite the opposite is true. The instruments take this role, as for example in the wind orchestras of Macedonia and Bulgaria.

Even very traditional songs such as the one that heard among Lovara and Kelderara contain this element. The usual repertoire in these groups consists mostly of ballads, sung by one or more person who improvises the text. In the chorus, when more than one singer is present, one almost always hears chords, that is, these three voices. Flamenco is maybe the only exception to this “rule”. Though in the Cante Rondo, this element is also present.

Timing

This element is the one that allows you to recognise a Rom playing in an orchestra, regardless of the kind of music or orchestra. It is the “attack” or beginning of the variations and song. Whereas in classical or, more generally, in Western music, a variation is always begun on the beat, Roma have a tendency to wait. To make matters somewhat clearer, they time their attack to start just after the beat, keeping the rhythm but nevertheless providing a rhythmic tension to the music.

Phraseology

This is the most subjective criterion. It is very difficult to provide a precise description of what Roma phraseology is. The point is, there’s one! The best analogy is the one of waves. This music is sung or played with intonations and small rhythmic stretches and compressions that reminds one of the passing of a wave. Depending on the country, a variation, be it vocal or instrumental can either begin as a forte and then decrease or as a medio voice and then to forte.

Harmonies

Most experts texts centre on this aspect of the Roma music. They speak about Gypsy scales, special harmonies and the like. One can explain it simply. When your musical mind and culture tells you to expect a major chord, Roma usually replace them with a minor chord. Not to say it always happens but it is very present in every song or melody. To take a simplistic example, consider the progression Dm – G – C in Dm. Next, you’d expect a major chord. Typically, you’ll get a minor such as Am.

Singing

Voices are an element which provides the last constant of Roma music. Again, it is not so much the technique of singing as the natural sound of the voices and the way it is used. Think about Flamenco and them listen to Russian Roma or even better, to Lovara songs. You’ll be astonished at the similarities in the sound of the voices and the way of singing.

Does this make Roma Music?

Well, does this “make” Roma music? Of course not. It just provides a thread by which one is able to deduce what is truly Romanes. Roma build a closed society to which access for a non Rom, a Gadžo, is truly difficult. Roma musicians, even though they have contacts with Gadže – after all, they mostly play for them – will choose a different repertoire than the one they will play among themselves. This Roma characteristic has biased many a study of Roma music. Just look at what is nowadays (and almost always has been) marketed as Gypsy music: Hungarian restaurant music is perhaps the best example. This is a style of music which, even though it displays some of the elements that have been described above[2], is what Roma call gadžikani muzika, music for the non Roma. It is Hungarian folk music played by Roma, nothing more, nothing less, played with a lot of flair and some specificities. This attitude is pervasive. Russian Roma have included Russian romances, Romanian Roma play Romanian folk tunes etc…

Repertoire

So besides the “characteristics”, there’s another component, the repertoire. One cannot easily explain this. What is truly old, truly Rrom and what is not? With the passing of time, with every year that Roma stayed in a given region, their music was influenced and they, in turn, influenced the local folklore. This accounts for the variety of styles, rhythms and musical traditions among Roma. In the Balkan, one feels the Turkish influence through the oriental rhythms. Flamenco reflects in part the Arabic culture that still shortly existed in Spain after the arrival of the first Roma. Is there a common ground? Or even a common source? Yes and this still exists and can be heard nowadays! So what is this “original”, or, to borrow a German word “Ur” music?

Roma ballads, mostly improvised and without rhythmic components, are the closest one can get to this original style. The Lovara have probably one of the closest relatives to this original form of music. Specifically in the music that you can hear when seated at a table with several of them. When they improvise on a theme, a toast or any other topic. Why can one claim this? Well, it is present among all Roma groups. Ask any old Rrom to sing you something, you’ll get at least one of these.

This is, of course not to say that some of the other songs are not a real Roma heritage. Some of them can be traced quite far back, in Russia, for example, through the literature. However, in many places, one cannot find archives or documentation. In those cases, one has to rely on one’s ears and soul to decide if that particular tune is old or new.

Richness

Richness of Roma music comes from its manifold forms. You can listen to many groups and song and still find something new, something which you hadn’t heard. Especially since it is a music which still evolves. Unfortunately, few people really know that music, even among Roma themselves. The old Roma generations are slowly disappearing and with them, an entire slide of Roma culture vanishes. To take a somewhat simplistic example, consider the Sinti. Their music is currently the one created by Django Reinhardt in the 1930’s as a blend of New Orleans Jazz and Blues and Sinti music. Who remembers nowadays what the Sinti used to sing and play before? This is a tragic event in the sense that in order to realise a successful blend – as Django did – one needs to have strong roots in ones own culture. Otherwise, what distinguishes the new blend from it source? It just become a plagiat.

Fact is, Roma music is an integral part of our European cultural heritage and it is worthwhile to know more about it!

[1] For lack of a better word, we have settled on groups for Kalderaša, Lovara, Sinti etc…

[2] Timing and Phraseology.